AFTERWORD

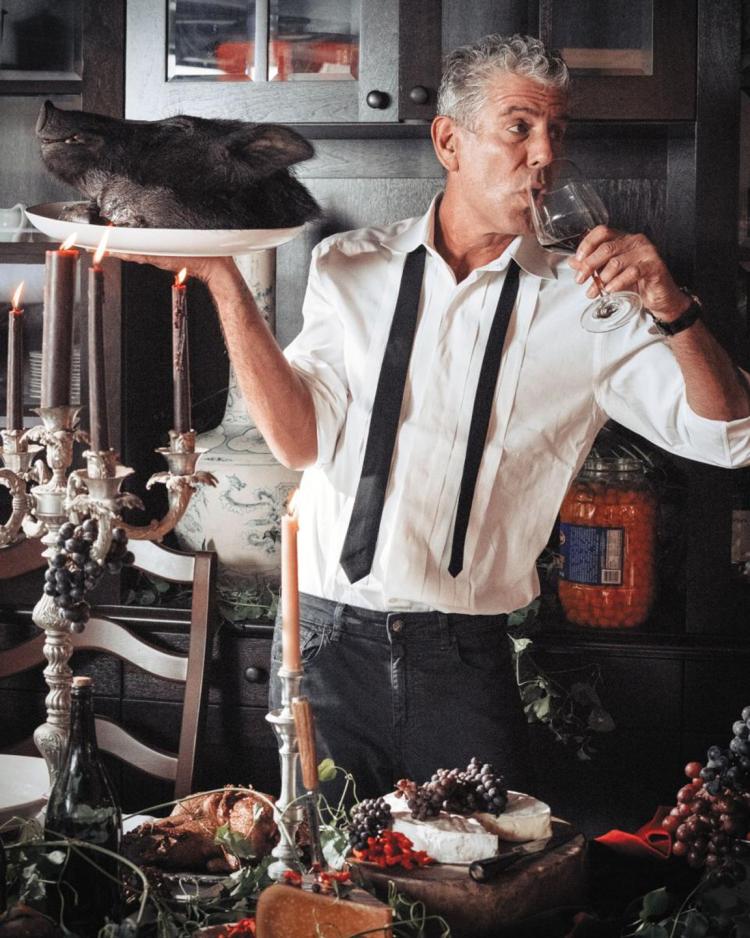

A Found Poem in Memory of Anthony Bourdain

I will always carry my heart around, my entanglements

a big room free of country, and most certainties.

My dreams travel in strange beauty, telling me what to do —

if I can relax or drink in fully, or if I have been comforted.

Beyond normal human itinerary, I don’t know absolutes.

Painful complexity — like a lot of wonderful nothing —

perfectly telling my way, after years, where and when.

Life still rules me. It says something, I think,

that I’m untormented by the cigarette, I don’t really

enjoy talking shit, I’m at home in the kitchen. I make

people skills every day, most relaxed when being nice.

I’m magnificent alone. I once knew a nice orderly life.

I’m less sure anymore, since upwards of ten or eleven

nights a month felt a mystery, somewhere southeast

of an Asia I don’t know, or a city lounge, a smoking

background — the Muzak there honest, four or five

complications I’ve had playing innocuously,

having maybe already captivated. I thought I knew the rules:

in-out-of, aren’t-weren’t, either-way. Live anywhere, man,

make a home, do my best full time, fully coming

from ‘safe’ adjustments. For one reason or another since,

maybe I’ve already told myself what to do: Be without,

challenge myself, relax in other months. Enjoy I don’t

know. So. Though human, behavior anymore, as it were,

has left the airport — a New-York-to-Asia-

twenty-eight-plus days of the year. On one hand, good;

all aren’t outside chefs. The particular world, then, remains

about true, and there at ease — another kitchen to me.

-Laura Scheffler Morgan, 11/28/18

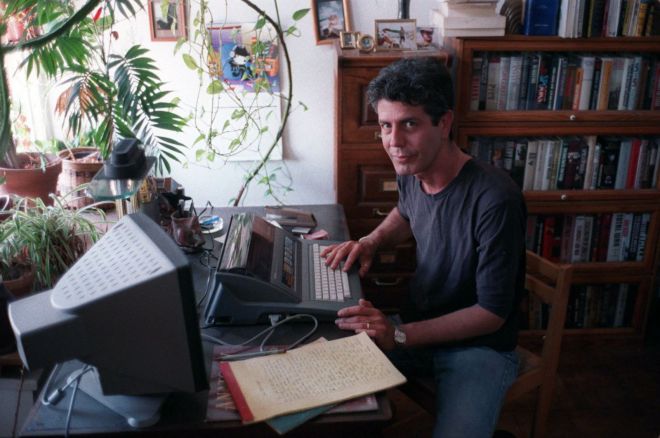

I wrote the above found poem in honor of Anthony Bourdain and his singular way of reaching people, whether or not he had obvious connections with them. I am one of those people he reached. I wrote the poem using only words from the following excerpt:

I don’t really live anywhere anymore, already a man without a country. I’m home – maybe – four or five nights a month and travel, for one reason or another, upwards of ten or eleven months out of the year. So maybe I’ve already left. Though I will always carry New York City around in my heart, I don’t know if I can fully relax and enjoy living there full time anymore, having been captivated in strange and wonderful ways by Asia, Southeast Asia in particular. I don’t know if I can relax and fully enjoy myself there either, to be perfectly honest. I once felt ‘safe’ and at home in the kitchen. I knew the rules – or thought I knew the rules. It was a life of absolutes – of certainties – and that comforted me in a way nothing since has. Like a lot of chefs, I’m less sure of myself outside the kitchen. Since all my dreams came true, I’ve had to make adjustments. I have to make them every day. My people skills – beyond telling them what to do – or being told what to do – and talking shit – weren’t the best after twenty-eight-plus years in The Life. They still aren’t. It says something about me, I think, that I am most at ease these days – at my most relaxed – when alone in the smoking room of an airport lounge, coming from somewhere nice and on my way to another. Muzak playing innocuously in the background, a nice orderly itinerary in one hand – telling me what to do, when to do it and where – a drink or a cigarette in the other… and I’m good. I’m free, as it were, of the complications of normal human entanglements, untormented by the beauty, complexity and challenge of a big, magnificent and often painful world.

Human behavior remains a mystery to me.

– Anthony Bourdain, Bali, 2006, from the Afterword of Kitchen Confidential, Updated Edition